Introduction

Last year, my world turned upside down in an instant. I contracted a rare flesh-eating bacteria that rapidly spread and required emergency surgery. The procedure itself went smoothly—at least at first. But later that same evening, I was jolted awake, overwhelmed by pain and panic. I was bleeding out. The medical team, in their rush to save my life, had forgotten to close an artery. I was seconds away from becoming another statistic, another case of medical oversight gone terribly wrong.

That night, I couldn’t help but think: If I, a relatively healthy individual, could nearly die due to human error, how many others face similar risks—quietly, unnoticed, every single day? This experience ignited a deep desire in me to better understand how we can minimize such risks, and it led me to develop a framework that has the potential to transform how patient safety is managed in healthcare.

This personal encounter became the driving force behind our Patient Safety Risk Model, a groundbreaking approach to managing patient safety risks by evaluating healthcare professionals’ capabilities and performance. Rather than focusing solely on system-wide protocols and checklists, this model zooms in on the capabilities and day-to-day performance of individual doctors, the very people who make life-or-death decisions every day. By understanding the interplay between a doctor’s professional capacity and daily performance, we can predict, prevent, and mitigate patient safety risks with precision.

The Current State of Patient Safety

Imagine stepping into a hospital as an invisible observer. In one corner, an exhausted resident nears the end of a 28-hour shift. Across the hall, a nurse juggles the care of six high-acuity patients, and in the emergency room, a surgeon makes a split-second decision amidst the chaos. This is the daily reality for healthcare professionals working under relentless pressure and limited resources. The toll is immense, with burnout rates soaring—44% of physicians show symptoms of burnout, and 57% of nurses report significant exhaustion.

The impact on patient safety is profound. Longer shifts and higher workloads increase the likelihood of preventable medical errors. A study in the New England Journal of Medicine found that shifts exceeding 12.5 hours led to a 36% increase in preventable errors. Traditional approaches to patient safety, focused on improving protocols and enhancing communication, have only yielded limited success. They often neglect the human element—healthcare professionals’ individual capacities, attitudes, and performance under strain.

Many current strategies also adopt a reactive approach, responding to safety incidents after they occur rather than identifying potential risks in advance. This reactive stance, though important for learning from mistakes, fails to prevent avoidable harm.

Our current system suffers from several key shortcomings:

- Fragmented View: We often analyze patient safety incidents in isolation, missing the broader patterns and systemic issues that contribute to risk.

- Reactive Stance: Many safety initiatives are implemented in response to adverse events, rather than preemptively addressing potential risks.

- One-Size-Fits-All Solutions: Standard protocols and procedures don’t account for the individual differences in healthcare providers’ capabilities and performance.

- Neglect of Human Factors: While we’ve made strides in improving systems and processes, we’ve often overlooked the crucial role of healthcare professionals’ individual characteristics in patient safety.

The gaps in our current approach necessitate a paradigm shift, one that focuses on the human drivers of healthcare. This is where the Patient Safety Risk Model comes into play.

Introducing the Patient Safety Risk Model

Imagine if we could identify which healthcare professionals are most at risk for patient safety incidents, not only understanding who is at risk but also assessing the likelihood and impact of potential violations. The Patient Safety Risk Model is designed to do just that. It is a strategic risk identification framework that evaluates whether practitioners possess the necessary skills, knowledge, attitudes, and behaviors to perform safely and effectively.

At its core, the Patient Safety Risk Model is a strategic risk identification and management framework designed to predict patient safety risks based on whether practitioners have the right skills, knowledge, attitudes, and behaviors to perform safely and effectively. It’s like having a high-powered microscope that allows us to zoom in on the individual components that contribute to patient safety, while simultaneously providing a panoramic view of systemic risks.

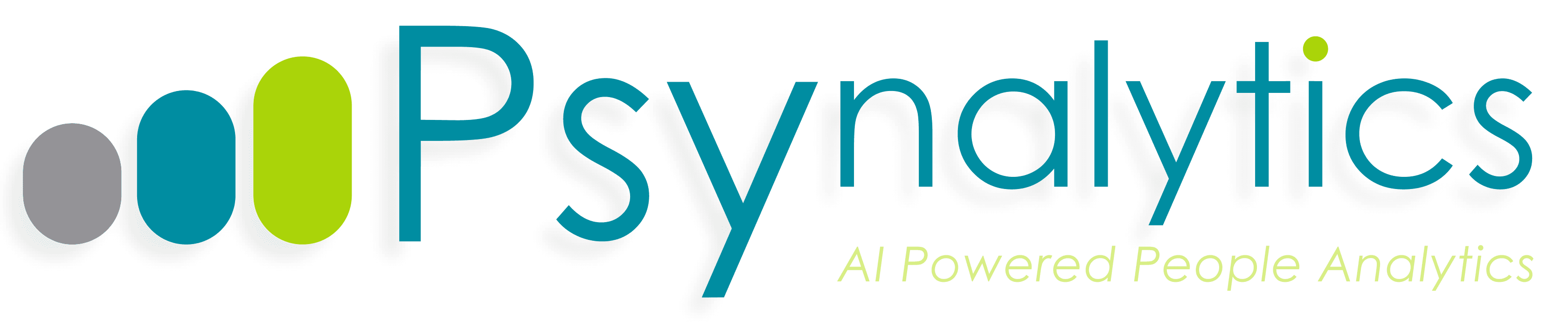

The model is built on an interplay between two fundamental pillars of risk: Professional Capacity and Performance of Medical Practitioners.

Professional Capacity is the bedrock upon which safe and effective healthcare is built. It refers to the qualities that enable a healthcare provider to deliver safe, high-quality care. It’s not just about what a healthcare professional knows—it’s about who they are and how they approach their work. The model breaks down Professional Capacity into three key components:

- Abilities: This includes analytical thinking, verbal reasoning, abstract reasoning, problem-solving, and technological proficiency. These are the cognitive tools that enable healthcare professionals to navigate complex medical scenarios and make sound decisions.

- Attitudes and Behaviors: Here, we’re looking at lifelong learning, multi-disciplinary collaboration, environmental agility, cultural sensitivity, stress management, and openness to experience. These factors shape how healthcare professionals interact with patients, colleagues, and the healthcare system as a whole.

- Knowledge and Skills: This encompasses clinical expertise, technical skills, systems thinking, medical knowledge, and ethical leadership. It’s the practical know-how that allows healthcare professionals to perform their duties effectively and safely.

Performance, on the other hand, is where the rubber meets the road. It refers to the practical application of these abilities, attitudes, and knowledge in delivering high quality healthcare. The model breaks Performance down into three critical areas:

- Clinical Excellence: This includes patient-centered care, clinical outcomes, quality and safety, and clinical decision-making. It’s about delivering top-notch medical care that puts patients first and achieves the best possible health outcomes.

- Operational Efficiency: This covers data-driven decision-making, resource utilization, time management, and cost-effectiveness. It’s about making the most of available resources to deliver care efficiently without compromising quality.

- Patient Satisfaction: This encompasses professional conduct, patient complaints, patient expectations, and relationship management. It recognizes that patient perception and experience are crucial components of healthcare quality and safety.

By examining the interplay between Professional Capacity and Performance, the Patient Safety Risk Model allows us to identify potential misalignments that could lead to patient safety risks. For instance, a healthcare professional with high capacity but low performance might be struggling with systemic barriers or personal issues that need addressing. Conversely, someone with lower capacity but high performance might be at risk of burnout or errors when faced with more complex cases.

What sets this model apart is its ability to not only identify potential risks but also to assess their likelihood and potential impact. This nuanced approach allows healthcare organizations to prioritize interventions and allocate resources more effectively. It’s no longer about implementing blanket safety measures, but about targeted, data-driven strategies that address the unique risk profiles of individual healthcare professionals and departments.

Moreover, the Patient Safety Risk Model bridges the gap between individual competence and systemic factors. It recognizes that patient safety is not solely dependent on individual healthcare professionals’ capabilities, but also on how well the healthcare system supports and enables their performance.

By adopting this model, healthcare organizations can move from a reactive stance to a proactive one, identifying potential risks before they manifest as patient safety incidents. It’s a shift from playing defence to playing offense in the critical game of patient safety.

As we delve deeper into the theoretical foundations and practical applications of this model, you’ll see how it has the potential to revolutionize patient safety management, ultimately leading to better outcomes for patients and healthcare professionals alike.

Theoretical Foundations of the Model

The Patient Safety Risk Model isn’t just an innovative idea—it’s a carefully constructed data-driven framework built on a solid theoretical foundation. The Model is based on the integration of 4 main psychological- and risk management theories. By integrating key concepts from these, the model provides a comprehensive approach to understanding and managing patient safety risks. Let’s explore the theoretical pillars that support the model.

Competence Theory

At the heart of the Patient Safety Risk Model lies Competence Theory. This theory emphasizes that professional capacity directly influences a healthcare provider’s ability to perform safely. Higher competence levels equip practitioners to handle complex medical cases more effectively, but competence alone is insufficient to prevent errors. The model accounts for this by recognizing the diverse nature of professional capacity, including cognitive abilities, technical skills, and behavioral traits. In healthcare, this theory takes on critical importance—a practitioner’s competence can literally be a matter of life and death.

Our model expands on traditional Competence Theory by recognizing that competence in healthcare is multifaceted. It’s not just about clinical knowledge or technical skills, but also about cognitive abilities, attitudes, and behaviors. This holistic view allows us to identify potential competence gaps that might be missed by traditional assessments.

For instance, a surgeon might have excellent technical skills but struggle with stress management or teamwork. The Patient Safety Risk Model would flag this as a potential risk factor, even if traditional competence assessments might overlook it.

Donabedian’s Model of Quality of Care

Avedis Donabedian’s seminal work on healthcare quality provides another crucial foundation for our model. Donabedian proposed that healthcare quality could be assessed by examining three categories: structure (the context in which care is delivered), process (the transactions between patients and providers), and outcomes (the effects of healthcare on patients).

The Patient Safety Risk Model incorporates this thinking by focusing on both the ‘structure’ (Professional Capacity) and the ‘process’ (Performance) in predicting patient safety outcomes. By doing so, it acknowledges that even highly competent professionals can falter if the care process is flawed, and conversely, that well-designed processes can help mitigate individual shortcomings.

Swiss Cheese Model of Error

James Reason’s Swiss Cheese Model provides a compelling visualization of how errors occur in complex systems like healthcare. This model posits that errors occur when multiple layers of defense fail. In this model, each slice of cheese represents a defensive layer against errors. The holes in the cheese represent weaknesses in these defenses. When the holes in multiple layers align, errors can pass through, leading to adverse events.

In the Patient Safety Risk Model, Professional Capacity and Performance represent two critical defensive layers. When both are strong, they create a formidable barrier against patient safety incidents. However, weaknesses in either area can create ‘holes’ that increase the risk of errors slipping through.

This integration allows us to identify potential vulnerabilities that might not be apparent when looking at capacity or performance in isolation. For example, a healthcare professional with high capacity but inconsistent performance might represent a ‘misaligned expert’—a unique risk profile that traditional models might overlook.

Enterprise Risk Management (ERM) Principles

The final theoretical pillar comes from the world of business and finance. Enterprise Risk Management principles provide the quantitative dimension to our model, allowing us to assess both the likelihood and potential impact of patient safety risks.

By applying ERM principles, the Patient Safety Risk Model enables healthcare organizations to stratify risks and prioritize interventions. For instance, a ‘critical liability’ (low capacity, low performance) might represent a high likelihood of errors with potentially severe impacts, warranting immediate intervention. On the other hand, an ’emerging talent’ (medium capacity, high performance) might have a lower risk likelihood but still require support to prevent potential burnout or decline in performance.

Integration of Theories

The true power of the Patient Safety Risk Model lies in how it integrates these diverse theoretical perspectives. By combining insights from psychology, healthcare quality assessment, error analysis, and risk management, the model provides a comprehensive framework for understanding and managing patient safety risks.

This integration allows us to:

- Assess individual healthcare professionals holistically, considering both their capabilities and their actual performance.

- Understand how individual factors interact with systemic processes to create or mitigate risks.

- Identify potential misalignments between capacity and performance that could signal emerging risks.

- Quantify and prioritize risks, enabling more effective resource allocation and intervention strategies.

By grounding the Patient Safety Risk Model in these established theories, we create a robust framework that can withstand scrutiny and provide actionable insights. It’s not just a new way of looking at patient safety—it’s a synthesis of best practices and cutting-edge thinking from across disciplines, all focused on the critical goal of enhancing patient safety in healthcare.

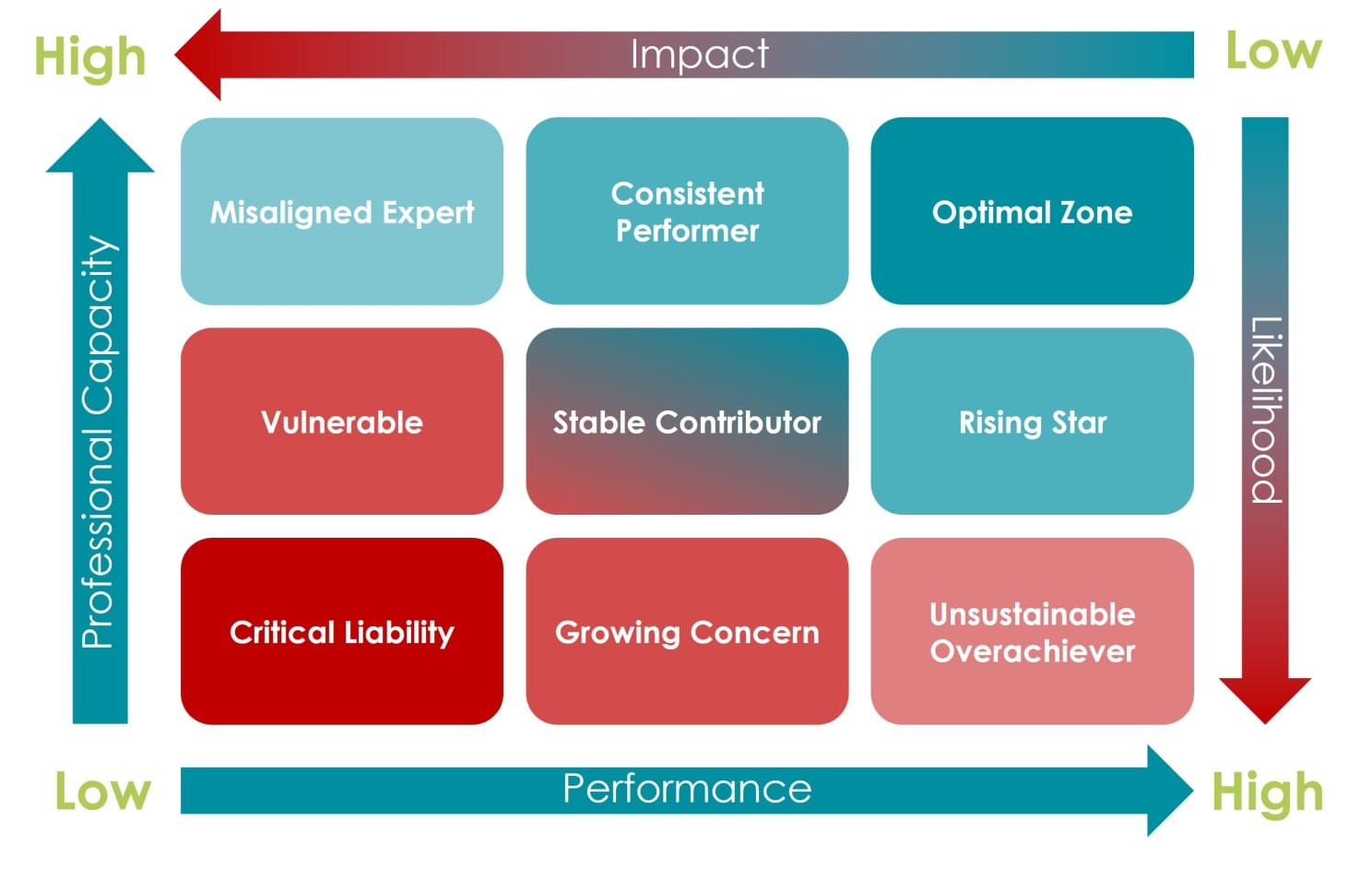

The Patient Safety Risk Matrix

Now that we’ve explored the theoretical foundations of the Patient Safety Risk Model, let’s dive into its practical application: the Patient Safety Risk Matrix. This 3×3 risk matrix is where theory meets practice. It provides a visual and intuitive way to categorize healthcare professionals based on their Professional Capacity and Performance.

In effect, the Patient Safety Risk Matrix operationalizes the model by allowing healthcare organizations to plot healthcare professionals and departments based on two axes:

- Professional Capacity (high vs. low)

- Performance Capacity (high vs. low)

On the opposite Y-axis is the Likelihood of making safety violations, and on the X-axis is the Impact of those violations. By plotting professionals along these dimensions, we can classify them into nine distinct categories or ‘profiles’, each representing different levels of risk.

Let’s explore each of these profiles in detail:

- Critical Liability (Low Capacity, Low Performance) This group represents the highest risk to patient safety. Healthcare professionals in this category lack the necessary skills, knowledge, and attitudes to perform effectively, and their actual performance reflects these deficiencies. They require immediate intervention, which may include intensive training, close supervision, or reassignment to less critical roles. The likelihood of patient safety incidents is high, and the potential impact could be severe.

- Growing Concern (Low Capacity, Medium Performance) These individuals are managing to deliver average performance despite low professional capacity, which is a precarious situation. While they’re currently meeting basic standards, there’s a significant risk of performance declining, especially when faced with complex cases or high-pressure situations. They need targeted development to enhance their professional capacity and sustainable performance.

- Unsustainable Overachiever (Low Capacity, High Performance) This is perhaps the most intriguing and potentially deceptive category. These healthcare professionals are somehow managing to deliver high performance despite low capacity. While this might seem positive on the surface, it’s likely unsustainable and poses a significant risk. They might be cutting corners, overworking themselves, or just getting lucky. The risk here is that their performance could suddenly plummet, especially in crisis situations. Immediate support is needed to boost their professional capacity to match their performance level.

- Vulnerable (Medium Capacity, Low Performance) These individuals have average capacity but are underperforming. This misalignment suggests that systemic factors or personal issues might be hindering their performance. They’re at a tipping point where a small decline in capacity could result in them becoming Critical Liabilities. Interventions should focus on identifying and addressing the barriers to their performance while also working to enhance their professional capacity.

- Stable Contributor (Medium Capacity, Medium Performance) This group represents the baseline or average in both capacity and performance. While they’re not an immediate cause for concern, there’s room for improvement. Regular monitoring and opportunities for growth should be provided to prevent slippage into higher-risk categories and to encourage progression towards the Optimal Zone.

- Emerging Talent (Medium Capacity, High Performance) These healthcare professionals are punching above their weight, delivering high performance despite only average capacity. While this is commendable, it also presents a risk of burnout or decline in performance if their capacity isn’t developed to match their output. They should be given ample opportunities for professional development to solidify and sustain their high performance.

- Misaligned Expert (High Capacity, Low Performance). This category represents a significant concern and a puzzling scenario. These individuals have high professional capacity—they possess the necessary skills, knowledge, and attitudes—but their performance is poor. This misalignment could be due to various factors such as burnout, personal issues, or systemic barriers in the workplace. The risk here is that their underperformance could lead to serious patient safety incidents, despite their high capacity. Interventions should focus on identifying and addressing the root causes of their performance issues, potentially including organizational factors that may be hindering their ability to apply their expertise effectively.

- Consistent Performer (High Capacity, Medium Performance). Healthcare professionals in this category have high capacity and deliver solid, if not exceptional, performance. While they’re reliable and pose a relatively low risk to patient safety, there’s untapped potential here. The focus for this group should be on identifying what’s preventing them from reaching optimal performance. This could involve providing additional resources, removing organizational barriers, or offering opportunities for them to fully utilize their high capacity.

- Optimal Zone (High Capacity, High Performance). This is the ideal category, representing healthcare professionals who are functioning at their best. They have high professional capacity and consistently deliver high performance. These individuals pose the lowest risk to patient safety and are likely to handle even complex or unexpected situations effectively. The challenge with this group is maintaining their high level of performance and preventing burnout. They should be recognized, rewarded, and potentially used as mentors or leaders to help elevate others.

The power of this matrix lies not just in its ability to categorize, but in how it guides targeted interventions and resource allocation. For instance:

- High-risk categories (Critical Liability, Vulnerable, Misaligned Expert) require immediate and intensive interventions to mitigate patient safety risks.

- Medium-risk categories (Growing Concern, Stable Contributor, Consistent Performer) need ongoing support and development to either maintain their current level or progress to lower-risk categories.

- Low-risk categories (Unsustainable Overachiever, Emerging Talent, Optimal Zone) require strategies to sustain their high performance and prevent burnout or decline.

Moreover, the matrix allows healthcare organizations to assess not just individual professionals, but also departments or specialties as a whole. Are certain departments clustering in high-risk categories? Are some specialties producing more Optimal Zone performers than others? These insights can guide systemic interventions and policy changes.

It’s crucial to note that this matrix is not a static tool, but a dynamic one. Healthcare professionals can and do move between categories over time. Regular reassessment is necessary to track progress, identify emerging risks, and adjust interventions accordingly.

The Patient Safety Risk Matrix also provides a framework for predictive analytics in healthcare. By analyzing historical data and trends, organizations can start to identify early indicators of category shifts. For example, what factors tend to precede a move from Stable Contributor to Vulnerable? Can we intervene earlier to prevent such shifts?

Lastly, this matrix offers a common language for discussing patient safety risks across an organization. It moves the conversation beyond individual incidents to a more holistic view of risk, capacity, and performance. This shared understanding can facilitate more productive discussions and collaborations between clinical staff, administrators, and risk management professionals.

In the next section, we’ll explore how healthcare organizations can practically apply this model and matrix to revolutionize their approach to patient safety.

Practical Applications and Implications

The Patient Safety Risk Model offers healthcare organizations a data-driven approach to managing patient safety. By assessing the professional capacity and performance of practitioners, the model identifies risks before they materialize into safety violations. This proactive stance can significantly reduce the number of preventable medical errors, improving patient outcomes and reducing organizational liability. But let’s explore how this model can be applied in real-world healthcare settings and and how it can be used to improve patient care.

Personalized Professional Development

One of the most immediate applications of the model is in tailoring professional development programs. Rather than a one-size-fits-all approach, organizations can design interventions based on an individual’s specific risk profile:

- For those in the ‘Critical Liability’ or ‘Vulnerable’ categories, intensive training programs focusing on core competencies and performance improvement can be implemented.

- ‘Misaligned Experts’ might benefit from coaching or mentoring to help them translate their high capacity into better performance.

- ‘Emerging Talents’ and ‘Unsustainable Overachievers’ could be offered accelerated development programs to quickly boost their capacity to match their high performance.

By targeting interventions in this way, organizations can make more efficient use of their training resources and see faster improvements in patient safety outcomes.

Risk-Based Resource Allocation

The model provides a data-driven approach to allocating resources for patient safety initiatives. Instead of spreading resources thinly across the board, organizations can focus on areas of highest risk:

- Departments with a high concentration of ‘Critical Liability’ or ‘Vulnerable’ profiles might receive additional staffing support or more frequent safety audits.

- Extra resources could be allocated to support ‘Unsustainable Overachievers’ to prevent burnout and potential safety incidents.

- ‘Optimal Zone’ performers could be leveraged as internal consultants or mentors to help improve overall organizational performance.

This targeted approach ensures that limited resources are used where they can have the greatest impact on patient safety.

Predictive Risk Management

By regularly assessing healthcare professionals and tracking their movement across the matrix, organizations can start to predict and prevent patient safety incidents before they occur:

- Early warning systems can be developed to flag when individuals are at risk of moving into higher-risk categories.

- Predictive analytics can identify patterns and factors that contribute to improved or declining performance, allowing for proactive interventions.

- Trend analysis across departments or specialties can highlight systemic issues that need addressing.

This shift from reactive to predictive risk management represents a significant leap forward in patient safety practices.

Enhanced Recruitment and Onboarding

The model can inform hiring decisions and shape onboarding processes:

- Recruitment assessments can be designed to evaluate both professional capacity and potential for high performance, helping to identify candidates likely to become ‘Optimal Zone’ performers.

- Onboarding programs can be tailored based on a new hire’s initial risk profile, ensuring they receive the right support from day one.

- Probation periods can be structured around moving new hires towards lower-risk categories in the matrix.

By starting with patient safety in mind, organizations can build a workforce that’s inherently safer and more effective.

Cultural Transformation

Perhaps the most profound implication of the Patient Safety Risk Model is its potential to drive cultural change within healthcare organizations:

- It shifts the focus from blame to development, recognizing that patient safety is a result of both individual and systemic factors.

- The model promotes a growth mindset by showing that risk profiles can change with the right support and interventions.

- It encourages open discussions about capacity and performance, breaking down silos between clinical practice and professional development.

- By providing a common language and framework, it facilitates better communication about patient safety across all levels of the organization.

This cultural shift can lead to a more open, supportive, and safety-conscious healthcare environment.

Challenges and Considerations

While the potential benefits of the Patient Safety Risk Model are significant, implementing it is not without challenges:

- Data Collection and Privacy: Regularly assessing professional capacity and performance requires robust data collection systems and raises important privacy considerations.

- Resistance to Change: Healthcare professionals may initially resist being ‘categorized’ or feel that the model oversimplifies complex issues.

- Resource Intensiveness: Implementing the model requires significant upfront investment in assessment tools, training, and potentially new roles focused on risk management.

- Avoiding Stigmatization: Care must be taken to ensure that the model is used as a development tool, not a punitive measure. The focus should always be on improvement and support.

- Maintaining Flexibility: While the model provides a structured approach, it’s crucial to remember that healthcare is complex and human. The model should inform decision-making, not dictate it inflexibly.

Despite these challenges, the potential benefits of the Patient Safety Risk Model in terms of improved patient outcomes, reduced incidents, and more efficient use of resources make it a compelling framework for healthcare organizations committed to excellence in patient safety.

As we look to the future of healthcare, models like this will be crucial in navigating the increasing complexity of medical care while ensuring the best possible outcomes for patients. The Patient Safety Risk Model doesn’t just offer a new way of managing risk—it provides a roadmap for creating healthcare systems that are safer, more efficient, and ultimately more effective in their primary mission: healing and saving lives.

Conclusion: Call to Action

As we stand at the crossroads of healthcare’s future, the imperative for change has never been clearer. The Patient Safety Risk Model offers us a powerful tool to transform how we approach patient safety, but its potential can only be realized through decisive action and unwavering commitment.

To healthcare leaders and policymakers, I say this: The time for incremental change has passed. We need bold, data-driven strategies that address the root causes of patient safety risks. The Patient Safety Risk Model provides a framework for this paradigm shift. Implement it in your organizations. Invest in the necessary infrastructure and training. Make it a cornerstone of your patient safety strategy.

To healthcare professionals on the front lines, your role is crucial. Embrace this model as a tool for growth and excellence. Engage actively in assessments, seek feedback, and commit to continuous improvement. Your growth isn’t just about professional development—it’s about saving lives.

To researchers and academics, we need your expertise to refine and expand this model. Conduct studies, gather data, and help us understand the nuances of how professional capacity and performance interact in real-world healthcare settings. Your insights will be invaluable in evolving this model to meet the complex challenges of modern healthcare.

To patients and patient advocates, demand more from your healthcare providers. Ask about their approach to patient safety risk management. Support institutions that adopt proactive, data-driven models like this one. Your voice can be a powerful catalyst for change.

Remember, every data point in this model represents a human life—a patient who trusts us with their care, a family counting on us to heal their loved one. We owe it to them to use every tool at our disposal to make healthcare as safe as it can possibly be.

The journey towards perfect patient safety is ongoing, but with the Patient Safety Risk Model, we have a compass to guide us. Let’s commit to this journey together, armed with data, driven by compassion, and united in our resolve to create a healthcare system where every patient receives the safe, high-quality care they deserve.

The lives of countless patients depend on the decisions we make today. Let’s choose wisely. Let’s choose progress. Let’s choose the path of data-driven, proactive patient safety management. The future of healthcare—and the lives of those we serve—depends on it.

References

Batt, A., Williams, B., Rich, J., & Tavares, W. (2021). A six-step model for developing competency frameworks in the healthcare professions. Frontiers in medicine, 8, 789828.

Cooper, J. B., Gaba, D. M., Liang, B., Woods, D., & Blum, L. N. (2000). The National Patient Safety Foundation agenda for research and development in patient safety. MedGenMed: Medscape general medicine, 2(3), E38.

de Heer, M. H., Driessen, E. W., Teunissen, P. W., & Scheele, F. (2024). Lessons learned spanning 17 years of experience with three consecutive nationwide competency based medical education training plans. Frontiers in medicine, 11, 1339857.

Donabedian, A. (2005). Evaluating the quality of medical care. The Milbank Quarterly, 83(4), 691–729. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1468-0009.2005.00397.x

Epstein, R. M., & Hundert, E. M. (2002). Defining and assessing professional competence. JAMA, 287(2), 226–235. https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.287.2.226

Gaba, D. M. (2000). Structural and organizational issues in patient safety: a comparison of health care to other high-hazard industries. California Management Review, 43(1), 83-102.

Kaplan, R. S., & Mikes, A. (2012). Managing risks: A new framework. Harvard Business Review, 90(6), 48–60.

Keijser, W. A., Handgraaf, H. J., Isfordink, L. M., Janmaat, V. T., Vergroesen, P. P. A., Verkade, J. M., … & Wilderom, C. P. (2019). Development of a national medical leadership competency framework: the Dutch approach. BMC medical education, 19, 1-19.

Leape, L. L., & Berwick, D. M. (2005). Five years after To Err is Human: What have we learned? JAMA, 293(19), 2384–2390. https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.293.19.2384

Lepre, B., Palermo, C., Mansfield, K. J., & Beck, E. J. (2021). Stakeholder engagement in competency framework development in health professions: a systematic review. Frontiers in medicine, 8, 759848.

Makary, M. A., & Daniel, M. (2016). Medical error—the third leading cause of death in the US. BMJ, 353, i2139. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.i2139

Maslach, C., & Leiter, M. P. (2016). Understanding the burnout experience: Recent research and its implications for psychiatry. World Psychiatry, 15(2), 103–111. https://doi.org/10.1002/wps.20311

Reason, J. (2000). Human error: Models and management. BMJ, 320(7237), 768–770. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.320.7237.768

Stander, F. W., & Van Zyl, L. E. (2019). The talent development centre as an integrated positive psychological leadership development and talent analytics framework. Positive psychological intervention design and protocols for multi-cultural contexts, 33-56.

van der Aa, J. E., Aabakke, A. J., Ristorp Andersen, B., Settnes, A., Hornnes, P., Teunissen, P. W., … & Scheele, F. (2020). From prescription to guidance: a European framework for generic competencies. Advances in Health Sciences Education, 25, 173-187.

van Engen, V., Buljac-Samardzic, M., Baatenburg de Jong, R., Braithwaite, J., Ahaus, K., Den Hollander-Ardon, M., … & Bonfrer, I. (2024). A decade of change towards Value-Based Health Care at a Dutch University Hospital: a complexity-informed process study. Health Research Policy and Systems, 22(1), 94.

Vincent, C., & Amalberti, R. (2016). Safer healthcare: Strategies for the real world. Springer Open. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-25559-0

Zouaoui, I., Drolet, M. J., & Briand, C. (2024). Defining generic skills to better support the development of future health professionals: Results from a scoping review. Higher Education Research & Development, 43(2), 503-520.